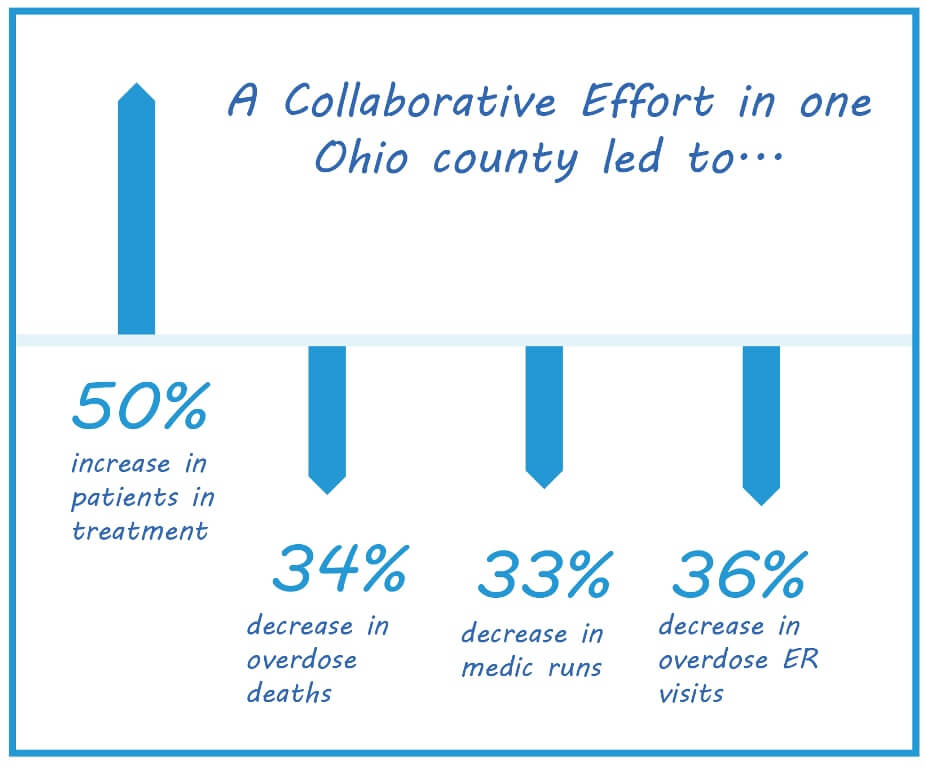

In the last several months, Hamilton County in Ohio, a diverse area that includes Cincinnati, has seen a 34 percent decrease in opioid-related deaths and a greater than 50 percent increase in the number of people receiving treatment.

That result begs the question: What is the medical community doing to address opioid use disorder (OUD) and overdose deaths that others can replicate?

The answer is two-fold. With a massive influx of Narcan (naloxone), they were able to stop people from dying at such high rates (the county recorded almost 600 opioid-related fatalities in 2017). With a new, streamlined approach with access to care, those who want treatment can now get it almost immediately.

The Addiction Treatment Collaborative began when a group of clinicians, recognizing that they were in the midst of a healthcare crisis, got together and began to talk about ways to mitigate the deaths. Three of the clinicians who helped develop the collaboration—Shawn Ryan, MD, MBA, ABEM, ABAM, President and Chief Medical Officer, Brightview; Larry Graham, MD, a Board Certified Psychiatrist and President, Behavioral Health Institute, Mercy Health; and Navdeep Kang PsyD, HSP, CGP, Director of Operations for Behavioral Health Services, Mercy Health—recently spoke with PCSS about the effort.

“I continuously asked the question, how in the world are we treating this life-threatening illness in a delayed fashion and acting like that’s okay,” says Dr. Ryan. Patients were being treated in the Emergency Room, then discharged with little to no follow-up. “It’s insanity that they wouldn’t try to see somebody immediately and receive life-saving medication assisted treatment.” Dr. Ryan, President of the American Society of Addiction Medicine’s Ohio State chapter (ASAM is a PCSS partner), started his career as an emergency physician and is now Board Certified in Addiction Medicine.

The two-pronged approach includes an urgent need for naloxone a drug that is used to revive those who overdose from opioids, including heroin. The group evaluated how much more naloxone would be needed to make an impact on the number of opioid deaths and concluded the county needed a 400 percent increase in the doses.

While naloxone had been used in the county prior to this effort, it was not available in the quantities or locations that it now is. Initially, the Narcan was donated by a pharmaceutical company, but they soon recognized they could not rely on donations alone. Working with pharmaceutical partners, community partners and healthcare systems, the county was able to fund the needed operational support needed. Access to naloxone became readily available from people leaving jail, entering treatment, being seen at syringe exchanges, and schools, universities, libraries, and faith organizations.

Meanwhile, the group worked to come up with methods to streamline the intake process for patients so that local treatment facilities could offer treatment on demand, rather than putting people on waiting lists for treatment. Though the naloxone was working to save lives, the larger issue was making certain they received evidence-based biopsychosocial treatment including medication assisted treatment. Brightview’s clinicians regularly take PCSS trainings to educate prescribers on evidence-based treatments for substance use disorder and OUD, Dr. Ryan said.

Prior to this effort, patients who either self-identified as having an opioid use disorder or those who were treated in the ER following an overdose often had to wait up to 4-8 weeks to see a anyone for treatment. “As the epidemic became more obvious and people were dying, it just didn’t make much sense to keep doing it like that,” says Dr. Graham.

The collaborative created a Request for Information for every treatment facility in the area that offered a full continuum of treatment and were certified by the state of Ohio to provide it (often through regular insurance benefits). They sent letters and followed up with a phone call, then called a meeting. Less than half the treatment centers contacted came to the meeting, but those that did were committed to the effort and to joining the collaborative.

They immediately focused on the main issue—wait times for treatment—and determined that two efforts were important to solving the problem: 24/7 intake and stream-lining the admission process BrightView put substantial work into ensuring a 24/7 hotline was operational so that patients could get appointments on demand. Also key to the effort was reducing the average time to perform patient intake. If the patient had come from a Mercy facility, all their information was already available, so Mercy, at its own expense, decided to share its electronic health records with all the cooperating treatment facilities. In part because of that effort, intake times dropped substantially, increasing providers ability to do intake.

The idea that OUD patients should and could be seen “on-demand” was not an easy sell in the beginning. “Historical standards clearly did not align with best practices,” Dr. Ryan says. “It took a lot of people speaking to this issue before it could come to fruition.”

Dr. Kang noted that once a patient has been revived, clinicians have a finite window to get them into treatment because waiting for treatment oftentimes results in the death of a patient from overdose. “All of us can tell you how frustrating it is when you’re trying to get a patient connected to a service that they need and you don’t have an answer for them,” Dr. Kang said. “Care transitions are particularly dangerous with this population. Folks drop out, lose motivation or feel discouraged.” Through communication and problem solving in real time, the collaboration has overcome many of its obstacles.

For another community to replicate what they were able to achieve requires total buy-in from the local healthcare system, treatment facilities, and local department of health. The Hamilton County Health Department was fully engaged and provided invaluable assistance in this effort—a key component to successfully rolling out the program.

The leaders of the collaborative laid the groundwork prior to launching the effort for more than two years. Members meet monthly to review share data and best practices, and while they group is gratified by their success, they did face obstacles along the way—obstacles that are diminishing as they see success. One of those obstacles was stigma within the medical community in treating patients with OUD.

“As far as stigma, I have to tell you, I underplayed that,” says Dr. Graham. “Obviously, you know there’s stigma out there, but I was surprised by how overt some of it was from our clinicians who just felt totally empowered enough to say, ‘Look, if they come in for second or third time, I’m not taking care of them.’”

Dr. Graham had a ready argument. “Would the same be true for the COPD patient if the third time they come in and they’re not breathing our plan is to say, ‘Look, you didn’t stop smoking so why don’t you come back when you quit smoking.’ Is that where we’re going?”

That argument has worked to change many clinicians’ mindset about treating patients who end up in the ER more than once from an overdose. “We have a mission to take care of these patients and we should be treating them like every other chronic relapsing condition,” Graham said.

What’s next for the collaborative? More of the same. The number of treatment facilities part of the collaborative is now 15 and the group is working to add more healthcare systems (Mercy Health System includes nine hospitals and five emergency rooms Hamilton County). Overdose deaths are still at an unacceptably high level, and while ultimately the collaborative may switch gears toward prevention, at the moment, the healthcare community is still in crisis mode.

“Our hyper focus needs to be on stopping the bleeding because the number of people who are dying is staggering,” Dr. Kang said.